To repeat, or not repeat, that is the question

Many new submarine cables have been announced by major Internet Content Providers, such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon, to interconnect data centers. These high-capacity submarine cables traverse oceans by leveraging the latest in wet plant and Submarine Line Terminating Equipment (SLTE) coherent modem technology… but what about the lesser known counterpart of these submarine cable designs, the unamplified submarine cables? I often get asked about unamplified submarine cable networks, so I thought I’d share some of my thoughts in this blog.

Amplifiers!

Due to the distances and capacities associated with transoceanic submarine cables, optical amplifiers are spaced at regular intervals along the cable to amplify information-carrying wavelengths. Undersea optical amplifiers are similar to their terrestrial counterparts, at least from an optoelectronic perspective, but are installed in one of the harshest telecom operating environments on Earth – the ocean floors, and sometimes several kilometers deep. Amplified submarine cables are more commonly referred to as “repeatered” cables, but this is actually a misnomer.

Repeaters?

A traditional optical communications “repeater” regenerates a received optical signal by performing 3Rs – Reamplify, Reshape, and Retime – to restore the quality of received optical signals, which involves OEO (Optical-Electrical-Optical) conversion. Repeaters, also referred to as “regenerators, or “regens” for short, were expensive and power-hungry devices, but were absolutely necessary for the proper transmission of information across great distances.

Fortunately, with the advent of ever-improving optical transmission technologies, we can now traverse thousands of submarine kilometers in the optical domain, by using Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers (EDFAs) and avoid the electrical domain along the way. OEO “repeaters” were rendered obsolete and removed from wet plant designs.

Figure 1: Traditional 3R (Reamplify, Reshape, Retime) OEO repeater

So, why do we now refer to optical amplifiers as “repeaters”? It’s related to history, and more likely, simply habit. For the remainder of this blog, I’ll refer to optical amplifiers with the commonly used misnomer, repeaters.

Amplified vs. unamplified submarine cables

Given the distances associated with transoceanic cables, from roughly 6,000km transatlantic to roughly 10,000km transpacific, there’s no choice but to use repeaters. However, for shorter distances, say a few hundred kilometers, you can submerge submarine cables, albeit without repeaters, which are commonly referred to as “unrepeatered” submarine cables. They’re also commonly referred to as passive, festoon, or single-span-loss cables.

Unrepeatered cables are commonly used to cross much shorter submarine distances, such as across lakes, rivers, fjords, or straits. They can include passive Branching Units (BUs) as well, to interconnect multiple shoreline locations in what’s commonly called “festoon” networks.

Unrepeatered submarine cable performance

Unrepeatered submarine cables commonly use (very) high-power optical amplifiers to launch at maximum allowable power levels, without damaging (melting) the fiber itself, and optical amplifiers at the receiving end such as EDFAs, Raman amplifiers, or Remote Optically Pumped Amplifiers (ROPA) to increase received power levels such that signals received can be successfully terminated. Similar to repeatered submarine cables, there are performance tradeoffs associated with unrepeatered submarine cables, primarily related to achieving maximum reach and maximum capacity. Unrepeatered submarine cables can achieve multiple terabits per second of capacity over hundreds of kilometers, although the performance will be application-dependent, same as for repeatered submarine cables.

“A long, submerged patch cable”

A network operator once told me he considered his unrepeatered submarine cable a “very long yet submerged optical patch cable”, which it is, as it’s essentially a very long passive optical fiber without submerged electroptics. This doesn’t mean it’s easy to achieve the desired performance, though. Maximizing capacity and reach using very high-power optics, without melting the fiber strands, is challenging. However, given the submerged part is passive, unrepeatered cables should last indefinitely, unless someone or something severs the cable, such as an anchor.

Festoon networks

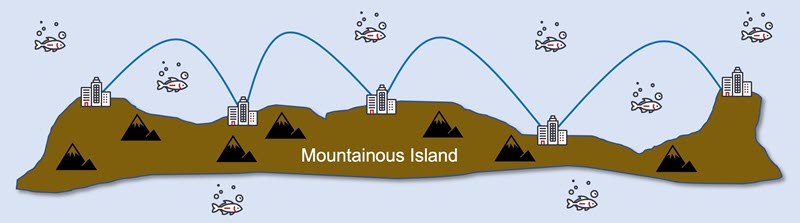

Although repeatered/amplified submarine cables get most of the fanfare these days, unrepeatered/unamplified submarine cables are just as important and serve a definite need by connecting landmasses over shorter distances. For example, “festoon” networks connect coastline locations using unrepeatered (passive) submarine cables to avoid terrestrial routes for a variety of reasons, such as challenging terrain (mountains), dense cities, and other reasons.

It’s often less expensive, and easier, to interconnect coastline locations via submarine routes. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below where multiple city centers are interconnected via unrepeatered submarine cables, because running fiber over mountains is too difficult and expensive. You could also use point-to-point radios, and this is indeed often the case in such scenarios, but if you want maximum upgradable capacity, then fiber optics is the only option.

Figure 2: Offshore festoon submarine cable network

Important to the global network infrastructure

Unrepeatered submarine networks are very important parts of the global network infrastructure, but they don’t receive nearly as much attention as more popular repeatered cables, likely because of the players, distances, and performance achieved on repeatered/amplified cables. If you want to cross aquatic distances up to a few hundred kilometers or want to avoid challenging costal terrestrial routes up to a few hundred kilometers, then unrepeatered submarine networks are a reliable, secure, high-capacity, and cost-effective option.

To repeater, or not repeat, that is the question. The answer is, unrepeatered where you can, repeatered where you must. Both configurations have their place in today’s global network and will continue to do so well into the future.